Air Operations, Bismarcks

43rd Heavy Bomb Group B-17s and 90th Heavy Bomb Group B-24s attack the Cape Gloucester and Gasmata airfields on New Britain and harbor areas around Rabaul.

[Air Operations, Europe

BOMBER COMMANDDaylight Ops:

- 60 Venturas are sent to bomb various targets in Belgium, Holland and France. Only 15 aircraft attack railway yards at Abbeville and the airfield at St Omer. 2 Venturas are lost.

- 263 aircraft are sent to Hamburg. Included in the total are 84 Halifaxes, 66 Stirlings, 62 Lancasters and 51 Wellingtons.

- Icing conditions over the North Sea cause many aircraft to return early. The Pathfinders do not produce a concentrated nor sustained marking on H2S and the bombing is scattered. The results in Hamburg are no better than the attack by a smaller force a few nights previous. Despite the weather, the German nightfighters give a good account of themselves.

- 16 planes are lost including 8 Stirlings, 4 Halifaxes, 3 Wellingtons and 1 Lancaster.

- 8 Wellingtons lay mines off Lorient and St Nazaire and there are 4 OTU sorties.

- 1 mine-laying Wellington is lost.

Air Operations, Mediterranean

XII Bomber Command B-26s attack Axis ships at sea between Sicily and Tunisia.

[Air Operations, New Guinea

V Bomber Command B-25s attack Wamar Island, and A-20s attack various targets between Mubo and Komiatum.

[Air Operations, Sicily

IX Bomber Command B-24s attack the harbors at Palermo and Messina.

[Air Operations, Solomons

US Navy and Marine Corps Cactus Air Force fighters and bombers, and 347th Fighter Group fighters, attack the Munda Point airfield on New Georgia. 4 VF-6 F4Fs down 1 G4M 'Betty' bomber at sea at 1216 hours. 4 other VF-6 F4Fs down another 'Betty' at sea at 1625 hours.

[Air Operations, Tunisia

- 15 XII Bomber Command B-26s attack Gabes Airdrome about 1100 hours. 82nd Fighter Group P-38 pilots, escorting the bombers, down 1 Ju-88, 1 Bf-109, and 2 twin-enging fighters.

- XII Bomber Command B-25s attacking bridges north of Maknassy claim severe damage on one rail span.

- XII Fighter Command A-20s attack tanks and motor vehicles in the northern ground-battle area and an artillery position and numerous trucks in the eastern Ousseltia Valley.

Battle of the Atlantic

- Flying in support of convoy HX-224 Fortress 'N' of No 220 Squadron sights U-265 through a gap in the clouds at a distance of about four miles. The aircraft drops 7 depth charges from 50 feet. Turning to make a second run the submarine had disappeared and all that remained was a spreading oil slick.

- U-223 attacks the Greenland-bound supply convoy SG-19 escorted by Coast Guard cutters Tampa (WPG-48), Escanaba (WPG-77) and Comanche (WPG-76), and sinks the War Department-chartered transport Dorchester about 150 miles west of Cape Farewell, Greenland. 675 men are lost on the Dorchester, including 15 of the 24 Armed Guard sailors. 4 Army chaplains, representing 4 different faiths, bravely gave up their lifebelts to soldiers who had not; all 4 went down with the ship. (See below)

- U-255 attacks Convoy RA-52 600 miles northeast of Iceland, torpedoing the US freighter Greylock (7460t). There are no casualties and the British escort trawler Lady Madeleine rescues all hands.

| Class | Type VIIC |

| CO | Oberleutnant zur See Leonhard Aufhammer |

| Location | N Atlantic, SW of Iceland |

| Cause | Air attack |

| Casualties | 45 |

| Survivors | None |

Burma

In the Arakan area the 123rd Indian Bde attacks Rathedaung but is easily repulsed by the Japanese. The latest British offensive in the Arakan around Donbaik and Rathedaung ends without success, as the Japanese hold on to the extremely strong defensive positions in the area.

[Eastern Front

- The Russians capture Kuschevskaya on the Soskya River 50 miles south of Rostov. In the drive to Kharkov Kupyansk, on the Oskol River, is taken. 3 Hungarian generals are captured at Voronezh.

SOUTHERN SECTORThe 40th Army joins the Voronezh Front offensive and advances up to 15 miles. Kupyansk falls to the 3rd Tank Army as the Germans retreat toward the Donets. Elements of the 3rd Tank push toward Pechengi. Farther south, units of the 3rd Guards Army enter Voroshilovgrad but are embroiled in heavy fighting as Group Fretter-Pico fights for every street. Fierce battles also rage at Slavyansk as XL Panzer Corps attacks 1st Guards Tank Army. Forces of Group Popov close upon Kramatorsk.

GERMANY: HOME FRONTThe defeat at Stalingrad is announced to the German people over national radio and three days' of mourning are declared.

[Germany, Home Front

Berlin acknowledges the end of the fighting at Stalingrad, saying that 'the sacrifices of the Army, bulwark of a historical European mission, were not in vain.' German radio announces that all theaters, cinemas, etc., will be closed for 3 days of national mourning begin on February 4.

[Guadalcanal

As dawn approaches the Japanese ships headed back up the slot. The are soon met by covering aircraft who were able to protect the retiring ships. The force reaches Shortland with their 5,000 evacuees the next day.

The 147th Infantry establishes a line extending south from Tassafaronga Point and patrols to the Umasani River, about 2,300 yards west of the Tassafaronga. The 2nd Battalion, 132nd Infantry, patrols northward toward Cape Esperance as far as Kamimbo Bay.

[New Guinea

Australian troops with strong artillery support drive off the Japanese in the Wau sector in the direction of Mubo.

[North Africa

TUNISIAIn the British 1st Army's US II Corps area, Combat Command D, 1st Armored Div, continues its attack toward Maknassy until directed to withdraw. It disengages and withdraws through Gafsa toward Bou Chebka, where it passes into corps reserve. Combat Command B arrives at Maktar and is held in British 1st Army reserve. The rest of the 1st Armored Div defends the region from Fondouk Gap to Maizila Pass, Combat Command C covering the northern sector from a point north of Djebel Trozza to the vicinity of Sidi Bou Zid and Combat Command A covering the area to the south as far as Djebel Meloussi. The 81st Reconnaissance Battalion is held in 1st Armored Div reserve at Sbeïtla.

[ Painting Showing Coast Guard Rescue |

|

| Through heroic efforts, the U.S. Coast Guard rescued 230 survivors from the USAT Dorchester when it sank on Feb. 3, 1943. This painting shows crewmen from the Coast Guard cutter Escanaba pulling men to safety. On June 13, 1943, the Escanaba itself was lost when it exploded and sank in the North Atlantic, cause unknown. (Courtesy of the United States Coast Guard) |

Clark V. Poling, who grew up in Deering, is one of the men whose names are engraved on the New Hampshire Marine Memorial at Hampton Beach. A minister in the Reformed Church in America, he enlisted in the U.S. Army as a chaplain in early 1942. Soon after completing training he was assigned to the USAT (United States Army Transport) Dorchester, along with fellow chaplains Methodist Minister George L. Fox, Reform-Rabbi Dr. Alexander D. Goode and Roman Catholic priest Reverend John P. Washington.

The Dorchester was built in 1926 as a civilian cruise ship. It was commissioned by the U.S. Army in February 1942 and converted into a troop transport vessel. The ship departed from New York City on Jan. 23, 1943, carrying 904 people (including its Merchant Marine captain and crew). The majority on board were army troops, but there was also a unit of Navy Armed Guards and a few civilian passengers. The Dorchester joined freighters SS Lutz and SS Biscaya, and Coast Guard cutters Tampa, Escanaba and Comanche, at St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada. Their destination was the Army Command Base at Narsarsuaq in southern Greenland.

On the evening of Feb. 2, 1943, the convoy was about 150 miles from Greenland. The sea was calm, the weather clear, and the air temperature was 36 degrees. The ships’ crews were put on high alert when the Coast Guard picked up a German submarine on sonar.

The soldiers on the Dorchester were ordered to sleep fully clothed, including wearing their life jackets. It is unlikely that many complied because their sleeping quarters were so stuffy.

At 12:55 a.m. on Feb. 3 the Dorchester was hit by a torpedo launched from German submarine U-223. It exploded well below the waterline, near the engine room. The ship’s lights went out immediately, and radio contact was cut off. The night was pitch black with no moon, and there were no flares or rockets to provide light until the Coast Guard cutters arrived. Men panicked in the total darkness, and many were trapped on the lower decks. Several lifeboats were smashed in the explosion. The ship listed sharply to starboard, preventing some lifeboats from being deployed, and others capsized due to overloading. There weren’t enough life rafts to go around.

The Dorchester sank, bow first, in about 25 minutes. Of the 904 men aboard, only 230 survived. Many of the men who perished succumbed to hypothermia within minutes in the 34 degree water.

The four chaplains went down with the ship. They gave their lives so that others would have a chance to live. Within the next several months, their dramatic story became widely known. As told in the New York Times on Dec. 3, 1944, the chaplains “made their way on deck and began circulating among the troops, encouraging them, praying with them and assisting them into lifeboats and life-jackets…Dorchester survivors credit the chaplains with the saving of many lives by their success in persuading confused men to overcome their fear and not plunge overboard…Many of the survivors recalled seeing the chaplains on the forward deck distributing lifebelts from a box. When the box was empty each chaplain removed his own priceless lifejacket and gave it to another man…The ship was sinking by the bow when the men in the water and in lifeboats saw the chaplains link arms and raise their voices in prayer. They were still on the deck together, praying, when the stricken ship made her final plunge.”

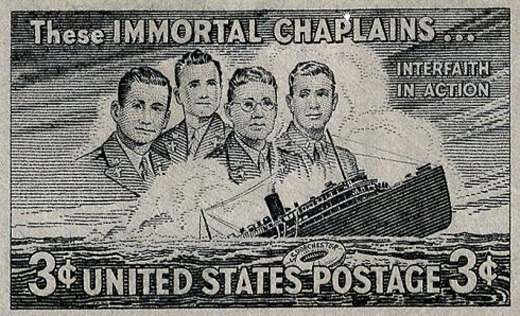

On Dec. 19, 1944, the “Four Chaplains” were posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross. Brigadier General William R. Arnold, chief of chaplains, honored them with these words: “The extraordinary heroism and devotion of these men of God has been an unwavering beacon for the thousands of chaplains of the armed forces.” In 1960, Congress authorized that they be honored with the unique “Four Chaplains’ Medal.”

There are many lasting tributes to the selfless actions of the “Four Chaplains” including chapels, monuments, charitable foundations and programs promoting inter-religious dialogue. Also, the names of First Lieutenants Poling, Fox, Goode and Washington are inscribed on the American Battle Monument Commission’s East Coast Memorial in New York City.

US postage stamp issued in 1948 to commemorate the "Four Chaplains" |

|