Battle of the Atlantic

Convoys

The convoy system had proven itself to be a valid concept during WWI. When the war broke out in September1939, shipping by convoys was rapidly organized. The first convoy, HX-1, sailed from Halifax on September 16th for an uneventful crossing. As war went on, convoys got to be more frequent and larger. The largest of all, HXS-300, was made up of 167 ships.

Great Britain required a very wide range of goods. Troops had to be carried overseas as well as all kind of military equipment – tanks, various types of vehicles, fuel, weapons. Food, lumber, building materials for barracks, and raw materials for the industry also came by boat. Plus all those goods that were already the object of a regular trade between the British Isles and North America before the war.

| Call Letters of Trans-Atlantic Convoys: | |

| HX: | fast convoys (9 knots or over) sailing from Halifax or New York |

| SC: | slow convoys (under 9 knots) sailing from Sydney, Nova Scotia, Halifax or New York |

| ON: | westbound convoys sailing from Great Britain to North America |

| ONS: | slow westbound convoys sailing from Great Britain to North America |

| Call Letters of Coastal Convoys: | |

| BX: | Boston to Halifax |

| XB: | Halifax to Boston |

| SQ: | Sydney to Quebec City |

| QS: | Quebec City to Sydney |

Convoy Organization

The faster a ship can cross the Ocean, the less risk she runs of being sighted and attacked by U-boats. But a convoy cannot be faster than its slowest member. The earlier convoys were too fast for older ships, which had to strain their engines to keep up with the other freighters. The slightest mechanical problem forced them to pull out of the convoy, thus becoming an easy target. To solve this problem, a two-speed system was implemented: fast convoys were still formed in Halifax harbour, but, starting August 15th, 1940, slower convoys regrouped in Sydney. In 1941, fast convoys left every six days and made the crossing to Great Britain in 13 or 14 days. Slow convoys left every six days as well but took up to 16 or 17 days to sail across the Atlantic. The meeting point was moved south to New York in September 1942.

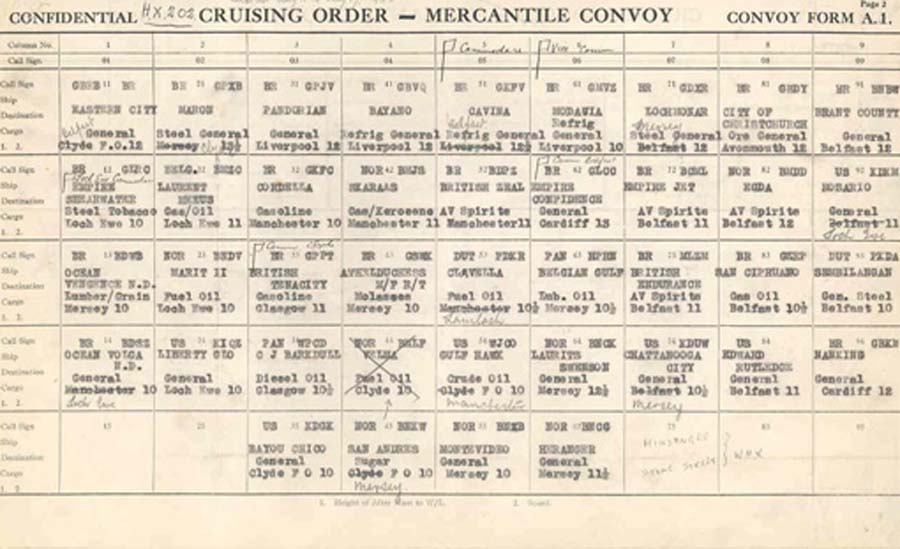

The forty – or so – ships that make up a convoy are positioned within a grid: there are nine columns, 920 metres apart, and in each column five ships, 550 metres apart. Ships carrying dangerous cargoes, such as gas, fuel, explosives are placed in the centre, the position that affords the most protection against enemy torpedoes. A convoy commodore, in most cases a retired naval officer, is on board one of the merchant ships to take defensive measures as required and ensure coordination with the escort.

Cruising Order of Fast Convoy HX-202 |

|

Naval authorities select the route, avoiding concentrations of U-boats, which crisscross the Northern Atlantic. Once the convoy has sailed off, it is joined by destroyers, corvettes and frigates, which position themselves on the periphery. A command ship precedes the convoy, while other escort ships take place on the flanks and astern of the convoy, in order to form a screen against submarines. Escort ships must keep their relative positions while making zigzags that allow them to sweep as broad an area as can be with the ASDIC detection system. At the end of the route, merchant ships leave the convoy in a pre-set order and continue towards their final destination, whether in England, Scotland or Northern Ireland.

A Dangerous Job

Between 1939 and 1943, even the Allies’ most extreme measures were not enough to ensure an efficient protection against U-boat attacks. Often at night, an explosion signalled that a merchant ship had been hit. The sailors aboard those vessels were well aware of how dangerous their work was. They knew they were targeted by enemy torpedoes. They also knew that some cargoes meant a sure death: a torpedoed tanker would blow up, a freighter carrying iron ore would sink before the men had a chance to escape.