Poland At 0445 hours the German forces invade Poland without a declaration of war. The operation is code-named Fall Weiss (Plan White). Appeals for reconciliation have been made by several small European countries including one by Leopold III of Belgium himself. Also, exhortations by President Roosevelt, prayers of Pope Pius XII and a last minute proposal for mediation by Mussolini all remain unanswered.

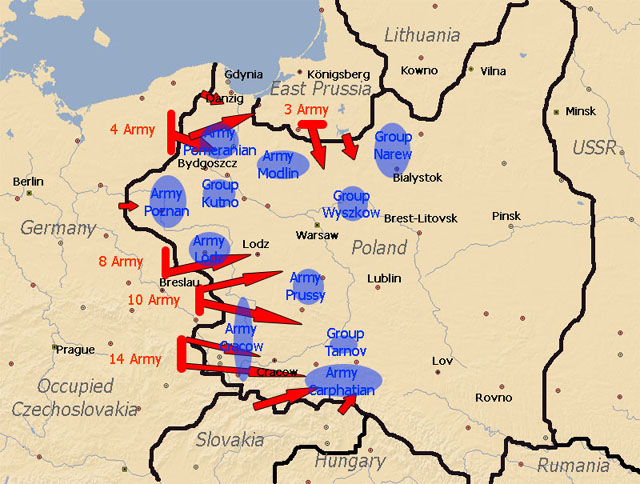

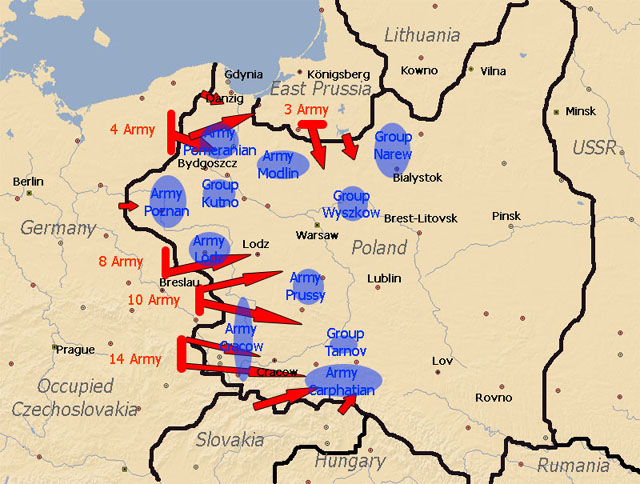

The Germans put 53 divisions into the attack, including their 6 armored and all their motorized units. Of the divisions left on the Western Front only about 10 are regarded by the Germans as being fit for any kind of action. Gen Walter von Brauchitsch, the Commander in Chief, is in full charge of the campaign and, indeed, will only meet Hitler on a few occasions in the course of the battles. Col-Gen Fedor von Bock leads Army Group North and Col-Gen Gerd von Rundstedt leads Army Group South. Bock's army commanders are Gen Georg von Küchler (4th Army) and Gen Guenther von Kluge (3rd Army). Runstedt's commanders are Gen Johannes Blaskowitz (8th Army), Gen Walther von Reichenau (10th Army) and Col-Gen Wilhelm List (14th Army). Heinz Guderian and Ewald von Kleist lead Panzer Corps. Air support comes from Albert Kesselring's and Alexander Lohr's Air Fleets which have around 1,600 aircraft. Von Runstedt's troops, advancing from Silesia, are to provide the main German attacks. Blaskowitz on the left is to move toward Poznan, List on the right toward Krakow and the Carpathian flank, while the principal thrust is to be delivered by von Reichenau who is to advance in the center to the Vistula between Warsaw and Sandomierz. Von Küchler from East Prussia is to move south toward Warsaw and the line of the Bug to the east. Von Kluge is to cross the Polish Corridor and join von Küchler in moving south.

The Poles have 23 regular infantry divisions prepared with 7 more assembling, 1 weak armored division and an inadequate quantity of artillery. They also have a considerable force of cavalry. (Although it is commonly believed, it is not true that cavalry will be used later in the campaign to charge German tanks.) The reserve units were only called up on August 30 and are not, therefore, mobilized as yet. In the air almost all the 500 Polish planes are obsolete and will be able to do very little to blunt the impact of the German attack. The Polish Commander in Chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly, has deployed the stronger parts of his army in the northwestern half of the country, including large forces in the Poznan area and in the Polish Corridor. Although there are few natural barriers favoring defense in the western half of the country (the dry summer weather confirms this), he hopes to hold the Germans to only gradual gains. By thus stationing his forces well forward and by the attacking tactics adopted, Rydz-Smigly has risked a serious defeat. Many units will be overrun before their reinforcements from the reserve mobilization can arrive.

The Poles have 23 regular infantry divisions prepared with 7 more assembling, 1 weak armored division and an inadequate quantity of artillery. They also have a considerable force of cavalry. (Although it is commonly believed, it is not true that cavalry will be used later in the campaign to charge German tanks.) The reserve units were only called up on 30 Aug and are not, therefore, mobilized as yet. In the air almost all the 500 Polish planes are obsolete and will be able to do very little to blunt the impact of the German attack. The Polish Commander in Chief, Marshal Edward Rydz-Smigly, has deployed the stronger parts of his army in the northwestern half of the country, including large forces in the Poznan area and in the Polish Corridor. Although there are few natural barriers favoring defense in the western half of the country(the dry summer weather confirms this), he hopes to hold the Germans to only gradual gains. By thus stationing his forces well forward and by the attacking tactics adopted, Rydz-Smigly has risked a serious defeat. Many units will be overrun before their reinforcements from the reserve mobilization can arrive.

The Germans cross the frontier at several points and their superior training, equipment and strength quickly bring them the advantage in the first battles. The Polish defenses are overwhelmed in a short time and the German tanks drive deep into enemy territory. The Germans also bomb several cities including Warsaw, Lodz and Krakow. At sea, as in the air, the story of Polish inferiority and crushing early attacks is much the same. 3 of the 4 Polish destroyers manage to leave for Britain before hostilities begin and later 1 submarine also escapes.

Schleswig-Holstein Fires on Danzig

|

|

|

|

The success of the invasion has been taken for granted by the Germans. The general lines of the partition of Poland have already been agreed upon in the secret clauses of the Russo-German pact of Aug 23. Generally speaking, the demarcation line between Germany and the USSR is to run along the lines of the rivers Nurew-Vistula-San. Lithuania is to be included in the German sphere of influence, while the Russian sphere includes Estonia, Latvia, Finland and Bessarabia (which is to be returned to Russia by Rumania).

[  ] ]

Britain, Home Front General mobilization is proclaimed. Because of the fear of air attacks the evacuation of 3 million women, children and invalids from London and other supposedly vulnerable areas is begun. Air Raid Precaution is introduced and the 'blackout' is enforced from an hour after sunset to an hour before sunrise. Street lights should be turned off and all windows covered with black material to hinder German bombers from finding their targets.

Children Waiting Evacuation by Train

|

|

|

|

|

Children Evacuated by Bus

|

|

|

|

|

[  ] ]

Diplomatic Relations Under terms of Mutual Assistance Treaties, Poland appeals for British and French intervention. Britain and France immediately demand a German withdrawal from Poland. The British army is mobilized. Italy announces that she will not take any military initiative.

[  ] ]

Tops in the Field

|

|

|

|

|

Poland Has No Chance

|

|

|

|

|

War!

|

|

|

|

German Forces Storm Poland

|

|

|

|

|

Map of Poland

|

|

|

|

|

The Terrifying Stukas

|

|

|

|

|

Bombing Aftermath in Wielun

|

|

|

|

|

Field Marshall Karl Rudolf Gerd von Rundstedt

|

| |

|

Before the Second World War, Wielun was a peaceful Polish town of about 15,000, located 12 miles (20 kilometers) from the German border. On September 1, 1939, at about 04:40 am, Stuka dive bombers of the German Luftwaffe attacked the town indiscriminately. Approximately 90% of the historic old town was destroyed, and many important buildings were hit, including the medieval Gothic church, the old town hall, and the hospital (despite a huge Red Cross sign painted on its roof). About 1,200 civilians died, representing 8% of the population.

The bombing of Wielun is considered one of the first terror bombings in history, and the very first in of World War II. The bombing had no military justification. Tactically, there were no Polish military forces stationed in Wielun. Strategically, the town held no heavy industry. German claims that the attack was a result of a mistake of the Nazi intelligence services (who reported that there was a Polish cavalry brigade stationed near the town) have been disproved. Officially, Poland recognizes the bombing of Wielun as a war crime.

|